This is a summary of my paper published in the March 2017 issue of The Journal of Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture. Download article.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of headache and affects up to 80 percent of people at some point in their life. It is a common cause of occupational absence and has a substantial economic impact; a longitudinal study revealed a 10 percent increase in the occurrence of tension-type headaches between 1989 and 2001.

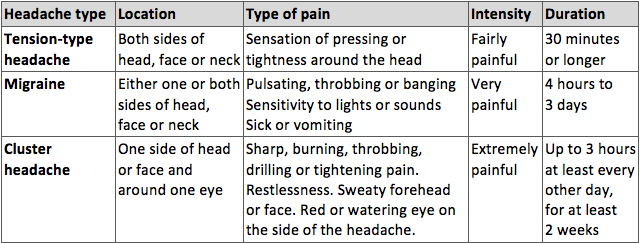

Western medicine distinguishes three types of primary headache: tension-type headache, migraine and cluster headache. These differ from secondary headaches that may have similar symptoms but are caused by an underlying health problem, injury or medication. Once the diagnosis of secondary headache has been ruled out, Tension-type headaches can be diagnosed and distinguished from other headaches as follows:

Types of primary headache

Little is known about the causes of tension-type headache but it is suspected that poor health status, stress and insomnia contribute to the condition. Tension-type headaches is commonly treated with painkillers. For sufferers of chronic headaches (pain on 15 or more days per month), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends up to ten sessions of acupuncture.

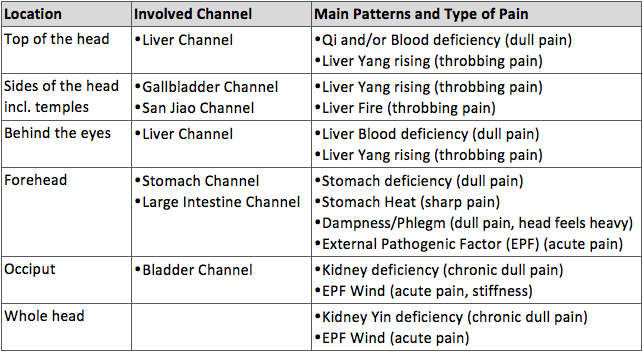

Headaches distinguished by acupuncturists

In diagnosing and treating headaches, acupuncturists distinguish between a number of factors, such as the nature and location of the pain, the acupuncture channels involved and the underlying patterns of disharmony.

Headaches by location, involved acupuncture channel, patterns and pain

In treating headaches, acupuncturists consider all the above factors and subsequently devise a treatment tailored to the unique combination of symptoms and underlying patterns present in a patient. That is, there is no standardised acupuncture treatment for headaches and the points needled will differ from patient to patient. Nevertheless, one might assume that, whatever the location of pain, practitioners will consider needling both points in the area of the pain and distal points on the hands and feet.

Findings

In order to assess the evidence on the efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of tension-type headaches, a systematic search for English language peer-reviewed research papers containing the words “acupuncture”, “tension” and “headache” in the title was conducted in February 2016. Six papers were identified that reported the outcome of a randomised controlled trial (RCT), whereby patients in the treatment group receive verum acupuncture and patients in the control group receive sham acupuncture.

All six studies conclude that both verum and sham acupuncture have significant clinical benefits for patients with tension-type headaches and help reduce the frequency and intensity of headaches, or the intake of painkillers. Yet which method is more efficient: verum or sham?

Two studies conclude that verum acupuncture is significantly more beneficial in the treatment of tension-type headache than sham;

Two studies conclude that although verum acupuncture appears to have benefits over sham, the differences are statistically not significant;

Two studies argue that the differences between verum and sham acupuncture are too small to be clinically relevant.

Overall, the results suggest that verum acupuncture is efficient in treating tension-type headaches and also appears to have an advantage over sham but, inevitably, more studies are required to resolve the discrepancies between the studies conducted to date.

Methodological pitfalls

An essential quality criterion for any RCT trial is that of validity, defined as the extent to which a concept is accurately measured in a quantitative study. That is, a survey designed to measure the efficacy of TCM acupuncture but which operates with a simplified notion of acupuncture could not be considered to meet the validity criterion. The above trials claim to measure the efficacy of TCM acupuncture and hence, in order for their findings to be valid, their methodologies must conform to those of TCM. This is important since the consequences of operating with an oversimplified notion of acupuncture would not only be detrimental to tension-type headache patients (who would not receive the best available treatment) but also negatively impact on the perception of TCM acupuncture in the Western scientific community.

I would like to highlight four methodological shortcomings of the above studies.

First, five of the six RCTs lack evidence of the application of TCM principles in the diagnosis or treatment of tension-type headache. These studies do not differentiate headaches by their location; affected acupuncture channels; its type; or cause.

Second, a key principle of TCM acupuncture is the individualised selection of points, based on the differential diagnosis of patterns and causative factors, the location and nature of pain and affected acupuncture channels. Ignorant of this imperative, five of the six studies involved the needling of fixed points; only one study allowed practitioners to select points freely. The very notion of fixed points is at odds with the TCM principle of tailoring treatments to the individual and the unique way in which his or her symptoms manifest.

Third, one might argue that in order to assess the efficacy of TCM acupuncture in the treatment of tension-type headaches, studies ought to be designed and carried out by TCM acupuncturists rather than Western medical doctors. All studies discussed above were conducted by Western medical doctors (neurologists, psychiatrists, anaesthesiologists) trained in acupuncture, but the extent to which they embrace TCM principles remains unclear.

Fourth, none of the studies discuss the peculiar role of placebo in acupuncture. From a TCM perspective, the placebo effect is both desirable and intrinsic to treatment success: the patient’s expectation to benefit from acupuncture aids relaxation, which in turns helps relieve Qi stagnation that is often implied in tension-type headache. Therefore, one might argue that in the studies discussed both “verum” and “sham” patients in fact received verum (albeit not necessarily TCM) acupuncture. Arguably, any needle inserted into the body will produce at least some physiological effect, that is, it will move Qi.

In conclusion, while all RCT trials claim to make statements about verum or TCM acupuncture, the above analysis suggests that this claim is largely unjustified. It is important to note that the needling of TCM acupuncture points does not necessarily constitute a TCM treatment. Rather, one might conclude that the studies discussed have measured the efficacy of an oversimplified notion of acupuncture, rather than of TCM acupuncture itself. Therefore, more and better-designed studies are required to assess the efficacy of TCM acupuncture in the treatment of tension-type headache.

This is a summary of my paper published in the March 2017 issue of The Journal of Chinese Medicine and Acupuncture. Download article.